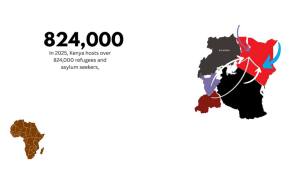

In 2025, Kenya hosts over 824,000 refugees and asylum seekers, according to UNHRC Organization, a growing number of whom are from Burundi and Rwanda. Most don’t arrive on front-page headlines. They walk. They ride. They blend. The East African Community’s free movement protocols were supposed to smooth cross-border movement—but for many, especially the undocumented, the journey remains anything but smooth.

They drifted through Nairobi’s bustling markets and barbershops, their presence subtle yet unmistakable, wielding scissors, selling fresh fruit, weaving between traffic on boda-bodas. For many of the Burundians and Rwandans now making a life in Kenya, their journey had begun years before, across borders shaped more by politics than people, across a region caught in the tug of conflict and opportunity.

In the suburb of Rongai, southwest of Nairobi, Jean-Paul Ndayambaje unpacked crates of bananas and kale with practiced rhythm. At 35, this Rwandan migrant ran a thriving grocery stand, more than a job, it was a quiet anchor in a life rebuilt from displacement. His arrival in Kenya had been legal, a student visa in hand and dreams of community development in his mind. But staying, really staying, had required much more than paperwork.

“Kenya gave me a home and a chance to grow,” Jean-Paul says. “Now I help others find their place too.”

That sense of helping others wasn’t just lip service. Over the years, Jean-Paul had guided dozens of fellow Rwandans—many undocumented—through the tangled bureaucracy of migration paperwork. He translated, advised, advocated. His leadership had become its own form of resistance: to fear, to alienation, to being invisible.

In 2025, Kenya hosts over 824,000 refugees and asylum seekers, according to UNHRC Organization, a growing number of whom are from Burundi and Rwanda. Most don’t arrive on front-page headlines. They walk. They ride. They blend. The East African Community’s free movement protocols were supposed to smooth cross-border movement—but for many, especially the undocumented, the journey remains anything but smooth.

The 824,000 refugees and asylum seekers hosted in Kenya as of 2025, based on UNHCR and related regional reports. While exact figures may vary slightly, the general breakdown typically looks like this:

By Country of Origin (approximate percentages):

| Country | Estimated Number | Approx. % |

| Somalia | ~287,000 | ~35% |

| South Sudan | ~178,000 | ~22% |

| DR Congo | ~54,000 | ~7% |

| Ethiopia | ~45,000 | ~5% |

| Burundi | ~26,000 | ~3% |

| Rwanda | ~15,000 | ~2% |

| Sudan (new arrivals) | ~18,000 | ~2% |

| Other countries (including Uganda, Eritrea, etc.) | ~201,000 | ~24% |

⚠️ Note: These numbers include both registered refugees and asylum seekers. A growing number are undocumented or in transit due to the porous East African borders and ongoing instability in their home countries.

By Location in Kenya:

| Location | Population Estimate |

| Dadaab Refugee Complex | ~240,000+ |

| Kakuma Refugee Camp & Kalobeyei Settlement | ~270,000+ |

| Urban Areas (mainly Nairobi) | ~80,000–90,000 |

| Unregistered/Undocumented (various towns) | ~220,000+ (estimate) |

“For a long time,” one Kenyan Redditor wrote, “barbershops… 80% are operated by Burundians. They even carry legit Kenyan ID.”

The truth, however, isn’t about deception. It’s about survival. Without passports, often unaffordable, or proper documentation, many migrants work informal jobs, unregistered, unprotected. In these shadowed spaces, they’ve built entire livelihoods, even communities. Nairobi’s Eastlands, Mombasa’s Old Town, Kisumu’s central markets, they all hum with their quiet resilience.

Despite challenges, something remarkable has emerged. Cultural blending, grounded in shared Swahili, food, music, and faith, has taken root. In some Nairobi neighborhoods, Burundian songs now mix with Kenyan street beats. In cafes, Rwandan tea rituals find new audiences. In churches and mosques, prayers rise in chorus across national origins.

Tatiana Mwikali, a youth organizer in Kibera, calls it “East African Afropolitanism.”

“You’ll see kids dancing to Congolese rumba on a matatu in Nairobi, while wearing Kigali streetwear and speaking Sheng. That’s what belonging looks like now.”

Yet, not all reactions are warm. Online forums bristle with comments about job competition and “illegal immigrants.” Xenophobia simmers, especially when public services like housing or healthcare are stretched. But others, especially younger Kenyans, see migrants as neighbors, coworkers, friends.

“They’re not a burden,” says Mwikali. “They’re a part of us.”

The economic footprint of this quiet migration is significant. Migrants are barbers, boda-boda riders, fruit vendors, mechanics, and nannies. Their remittances support families back in Burundi and Rwanda. Their taxes, though often informal, feed local economies. Some, like Jean-Paul, even mentor others into entrepreneurship, building grassroots economies from the ground up.

The biggest obstacle, however, isn’t cultural, it’s legal.

Without proper documents, many live in fear of detention or deportation. Statelessness, particularly among Rwandans descended from families displaced before the 1994 genocide, remains a hidden crisis. They are born, raised, and schooled in Kenya—but lack ID, citizenship, or recognition.

In 2023,a report released by East African Magazine, Kenya granted refugee status to only 34,426 people, far fewer than neighboring Uganda. The slow bureaucracy leaves many in limbo for years.

“One time, I was stopped while delivering bananas,” Jean-Paul recalls. “Even with my work permit, I was taken to the police post. It reminded me how fragile everything is.”

Still, hope persists.

Migrants like Jean-Paul are building more than businesses, they’re building bridges. They’re helping shape a regional identity that transcends borders, rooted in shared struggle and shared dreams. Their presence reminds Kenya, and East Africa, that migration isn’t a crisis. It’s history. It’s humanity. It’s the future.

In Kibera, youth groups now organize language exchange meetups. In Rongai, barbers from Burundi train local apprentices. In Mombasa, Rwandese church choirs sing with Kenyan congregations.

“None of us are ever fully free from having to pack a suitcase and leave,” says Jean-Paul. “But we can be free to arrive somewhere—and be welcomed.”

If migration is inevitable, then integration must be intentional. Kenya has an opportunity to lead East Africa into a new era—where intra-African migration is no longer something to hide or fear, but to support, regulate, and celebrate.

Through Streamlined documentation and permit systems, Inclusive refugee policies, building on the 2024 Shirika Plan, Urban support programs for housing, healthcare, and schooling, Youth-led employment and training initiatives and Statelessness recognition and resolution.

The migration of Burundians and Rwandans to Kenya is not just a statistic. It’s a story of ambition, resilience, and shared future. From barbershops to fruit stalls, from refugee camps to college dorms, they are quietly redefining what it means to belong in East Africa.

The challenge now is not whether to welcome them—it’s how to ensure they’re recognized, supported, and allowed to thrive. Because when they thrive, we all do.

~Kevinne Mullick

Founder Kgill Plus Media Hub.